5 Questions to Ask Before You Stop Accepting Medicaid Patients

Despite President Donald Trump’s attempts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—aka Obamacare—there’s been no substantive changes in 2017, including Medicaid eligibility.

Individuals and families who earn incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level are now eligible for Medicaid coverage. The goal of this expansion is simple: to provide health insurance coverage to more Americans. But some worry it could have the opposite effect.

Low physician reimbursement rates make Medicaid patients less financially attractive to medical practices. And many fear the influx of newly-insured patients will outpace the volume of doctors who can care for them, leading to a physician shortage.

As a result, many doctors with their own practices wonder if they’d be better off getting out of the Medicaid game altogether; an issue both doctors and patients are concerned about.

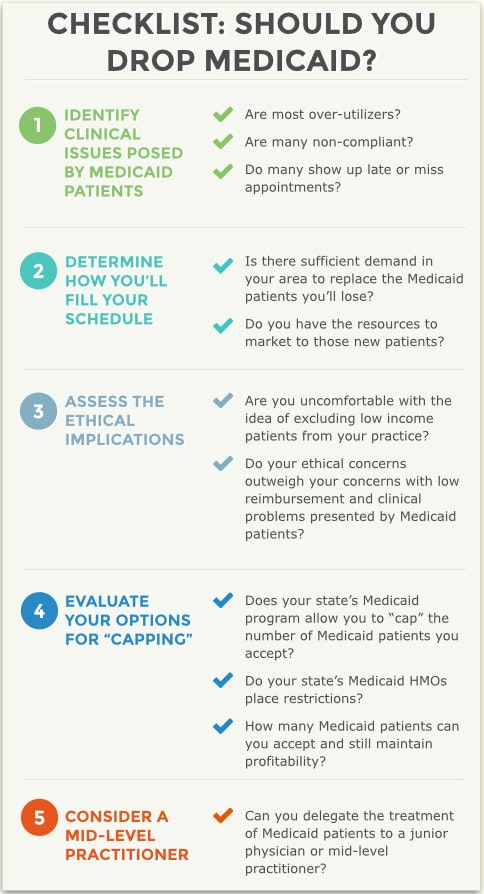

If you’re a doctor wondering if you should stop accepting Medicaid patients, there are a few questions you should ask yourself before making a decision.

1. What issues, other than reimbursements, do Medicaid patients pose?

The biggest problem for most physicians is that Medicaid reimburses at a much lower rate than commercial insurers. In many cases, doctors report it costs them more to treat a Medicaid patient than what they receive in reimbursement.

Many doctors don’t feel comfortable making a decision to stop seeing patients on a financial basis alone. But money isn’t the only problem—Medicaid patients can also present significant administrative hurdles.

Dr. Judi Cinéas is a psychotherapist practicing in Palm Beach, FL. “One of the biggest drawbacks of accepting Medicaid [patients]…is that they also require a lot more,” she says, citing more extensive documentation requirements, continuous preauthorization requests and annual audits.

A 2013 Health Affairs study also highlights physician concerns regarding what’s involved in Medicaid patient care. Some doctors report that their Medicaid patients are more medically complex, require longer office visits, comply with treatment less often and/or show up late for or miss appointments more often than commercially insured patients.

David Zetter, founder of Zetter HealthCare and a member of the National Society of Certified Healthcare Business Consultants, regularly consults with practices to help them improve business operations. The doctors Zetter works with regularly, he says, “will tell you [Medicaid patients] are the ones they earn the least amount of money on, but spend the most amount of time on.”

He echoes concerns about missed appointments and says non-payment is also an issue, which often results from a confusion on the part of Medicaid patients concerning their ultimate financial responsibility.

Of course, as Zetter points out, every patient is unique: not all Medicaid patients will pose problems beyond the low reimbursement rates. Both in and out of the Medicaid program, you’ll have some patients who simply require more from you and your staff than others, so you should analyze the behaviors of your Medicaid patient population and the staff resources required to manage them.

To do so, Zetter recommends asking yourself the following questions:

Are most of my Medicaid patients over-utilizers?

Are many non-compliant with treatment?

Do they show up late or miss appointments, frustrating staff and disrupting appointment times for other patients?

If the answer to more than one of those questions is yes, it’s time to reevaluate your participation in the Medicaid program.

2. How will I fill my schedule without Medicaid patients?

At this point, you may be thinking the decision to drop Medicaid is a no-brainer—after all, if you’re making less money and your patients are causing issues beyond reimbursement, why would you continue? But before you decide, cautions Zetter, you need to consider how your decision will impact every part of your practice.

One mistake physicians make when they decide to stop participating in Medicaid is not having a plan for filling the scheduling holes left by Medicaid patients.

You need to have an idea of whether there’s sufficient demand from commercially insured patients in your community who are not currently part of your practice. In other words, are there patients out there your practice can attract for whom you’ll receive the same reimbursement rate (or higher) than your Medicaid patients?

Assuming the answer is yes, you’ll also need the resources to market yourself to these existing patients. Without the confidence that you’ll be able to recruit these new patients, it doesn’t make sense to stop seeing Medicaid patients, Zetter says.

Dr. Cinéas points out a related question to ask yourself: “Am I trying to grow my practice?” The best incentive Medicaid has to offer, she says, is access to a huge patient population. If you’re a new practice, or looking to expand your existing practice, Medicaid can help.

“As a practice-builder, being a Medicaid provider is great,” Dr. Cinéas explains. If you’re willing and able to put in the hours required to treat them all, Medicaid can provide you with the patients you need.

3. Am I comfortable with the ethical implications?

For some practices, the answer to this question may trump all the rest. There are many who see a refusal to accept Medicaid as denying care on the basis of income, which many doctors simply aren’t comfortable with.

Dr. Cinéas, for example, feels a certain moral imperative to care for the lower-income patient population. “We have to understand that Medicaid patients also do need services,” she says.

This is what economists call a collective action problem. As a group, physicians may collectively agree that low-income patients also need care. But a single individual’s actions won’t make or break the outcome—and what’s more, this action comes at a personal cost—so individuals aren’t incentivized to act in a way that aligns with the group’s goals. “If I don’t pick up the slack, others will,” the thinking goes.

Dr. Cinéas points out the obvious flaw here: if every physician stops accepting Medicaid patients, this entire patient population wouldn’t receive medical care. It’s not just about the bottom line or the numbers, says Dr. Cinéas. “We have to remember that each number represents a person [who needs care].”

For doctors who see their role as something akin to a healer of the needy, dropping Medicaid patients goes against their responsibility as a physician. So if the answer to this question is a resounding “no”—regardless of any other factors—now may not be the time for you to consider leaving the Medicaid program.

4. Can I stop treating only some Medicaid patients?

For doctors who can’t stomach the idea of refusing treatment to all Medicaid patients, but whose bottom lines can’t withstand a high volume of them, there may be a compromise. For Dr. Cinéas, the answer lies in each practitioner shouldering a small part of the burden.

She suggests capping the number of Medicaid patients in your practice so you’re still providing some care to them, but at a manageable level. “Having the right balance of Medicaid and non-Medicaid clients allows [practitioners] to still be able to earn income and provide quality service,” she says.

Zetter also mentions this possibility, but cautions that limiting your patient panel is dependent on your state’s Medicaid requirements, as well as the requirements of commercial carriers participating in Medicaid HMOs.

In most states, he says, you’re allowed to cap the number of Medicaid patients you accept, but there will likely be guidelines around how you can do this, and each Medicaid HMO may have different rules.

If you do wish to limit your panel of Medicaid patients, you should be thoughtful about how many patients you can afford to treat. For Dr. Cinéas, determining the “cap” for her practice is a combination of her target earnings and how many hours she wants to work.

While there isn’t a one-size-fits-all calculation for practices trying to determine what that cap should be, important considerations include:

How much money do you want to make?

How much time do you spend in an average patient visit?

How long are you willing to be in the office each day?

How much are you reimbursed for various Medicaid procedural codes, and how does that compare to commercial reimbursement?

While limiting your Medicaid panel may help, know that it’s not a quick fix, and will require a good deal of administrative finagling on the front end. Zetter says you should start by communicating with your state’s Medicaid program and your Medicaid HMOs to determine their requirements and limitations.

5. Can I delegate care of Medicaid patients to a mid-level practitioner?

Another possible compromise scenario Dr. Cinéas suggests is using new physicians or mid-level practitioners, such as physician assistants or nurse practitioners, to manage Medicaid patients. These individuals typically earn lower salaries than the physician who owns the practice, which means you can lower your practice’s administrative costs by delegating the treatment of Medicaid patients to them.

This, of course, raises its own ethical questions—a fact that isn’t lost on Dr. Cinéas. The problem, she points out, is that this can leave Medicaid patients perpetually receiving care from the newest, most junior or most inexperienced practitioners.

The assignment of junior or mid-level practitioners to the treatment of Medicaid patients is a suggestion reluctantly supported by Dr. Susan Hall, a dentist in Kansas who’s quoted in a Kansas Health Institute report that focuses on the dental care of Medicaid patients in her state.

While Dr. Hall doesn’t readily support expanding the role of mid-level practitioners, she suggests that doing so—and allowing these mid-level practitioners to treat Medicaid patients—is preferable to low-income patients simply not receiving care.

Other Considerations

There are a few other things to keep in mind as you assess whether you want to continue treating Medicaid patients in your practice.

Medicaid Meaningful Use Incentives. If you’re participating in the Medicaid Meaningful Use EHR Incentive Program, you’ll need to continue treating Medicaid patients in order to receive the increased reimbursements from the government. (Eligible medical professionals can participate in either the Medicaid Meaningful Use Program or the Medicare Meaningful Use Program. Medicare incentives max out at $44,000 per practice, while Medicaid incentives go up to $63,750 per practice.)

Eligibility for Increased Medicaid Reimbursement. If you’re a family physician, internist, pediatrician or subspecialist in any of those fields, you were likely eligible for the increased Medicaid reimbursements that began in 2013 and are scheduled to run through the end of 2014.

These ACA-enacted increases raise Medicaid reimbursements for eligible providers (physicians for whom 60 percent or more of the Medicaid codes they billed in 2012 were primary care codes, as identified by the ACA) in an effort to encourage more physicians to treat Medicaid patients.

According to an Advisory Board report, some states’ Medicaid reimbursement rate more than doubles as a result of the legislation, and most states see a double-digit increase. But the increased reimbursement is only funded through the end of 2014, at which time states will have to come up with their own funding in order to continue. Zetter says most states probably won’t be able to maintain the higher rates, meaning reimbursement will drop back down to 2012 levels.

Patient Abandonment. If you want to discharge some of your Medicaid patients to bring your Medicaid volume down, you’ll need a valid reason—Zetter mentions patients who repeatedly miss appointments, don’t comply with care or don’t pay their bills.

You’ll also need to follow your state’s patient abandonment rules. This usually involves giving the patient advanced notice in writing, and possibly even suggesting other providers they might receive care from in your stead. Failure to do so can put you at serious legal risk.